Talk to Your Kids about the Lessons in Books

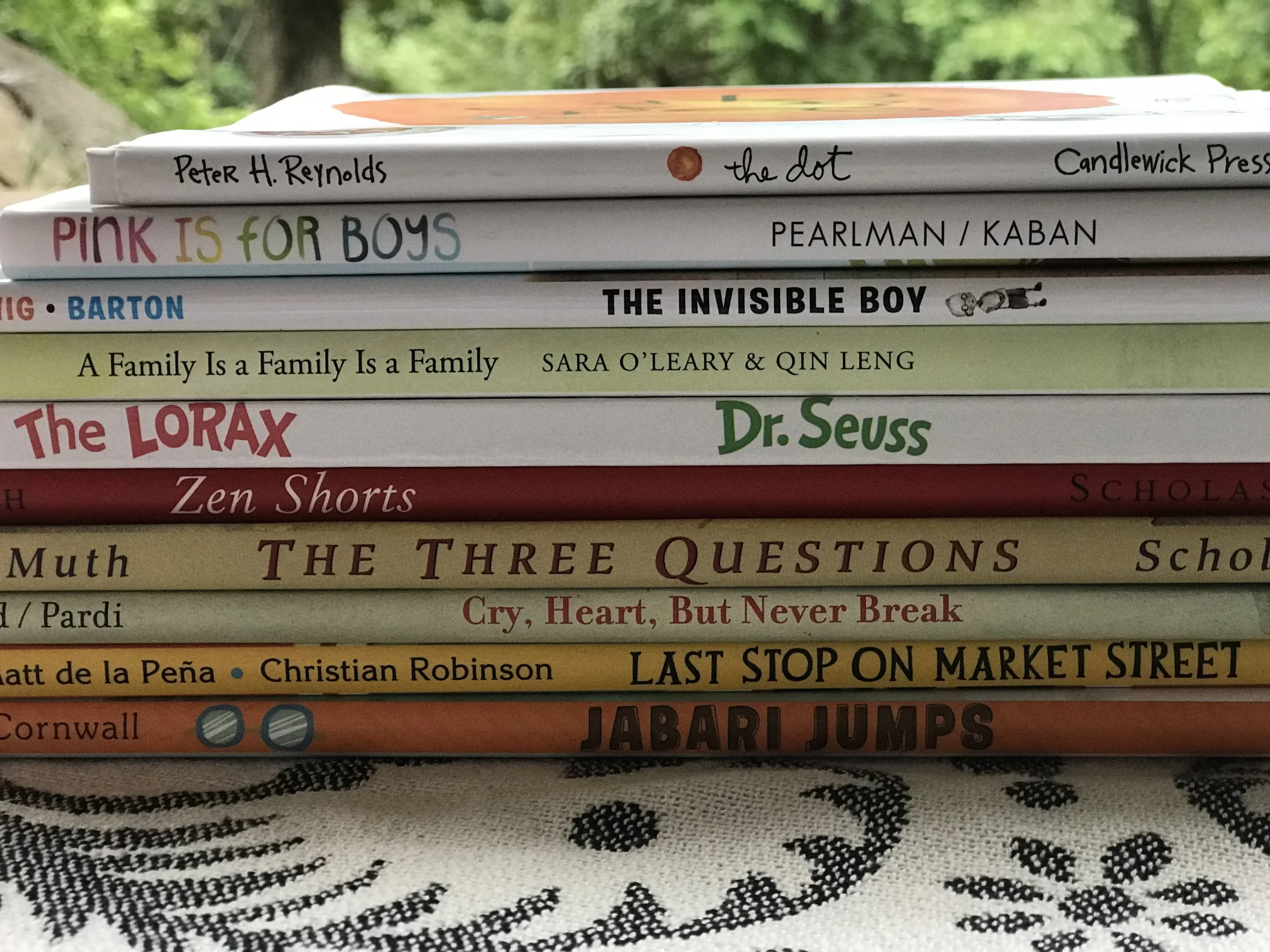

Stories that have moral lessons at the end go back as far into history as storytelling itself. Books have always been the perfect medium for teaching kids about more complex emotions and concepts - things like the importance of empathy or honor. But what if the moral of the story somehow gets lost along the way?

Through a bit of trial and error, I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s surprisingly easy to overestimate a child’s ability to always pick up on all the context clues of a story and extract all of the intended lessons. We as adults are able to draw on years of experience to correctly identify tricky concepts like sarcasm - and for the same reason we quickly recognize recurring patterns with characters and storytelling structures as well. But young children do not have the same luxury of experience.

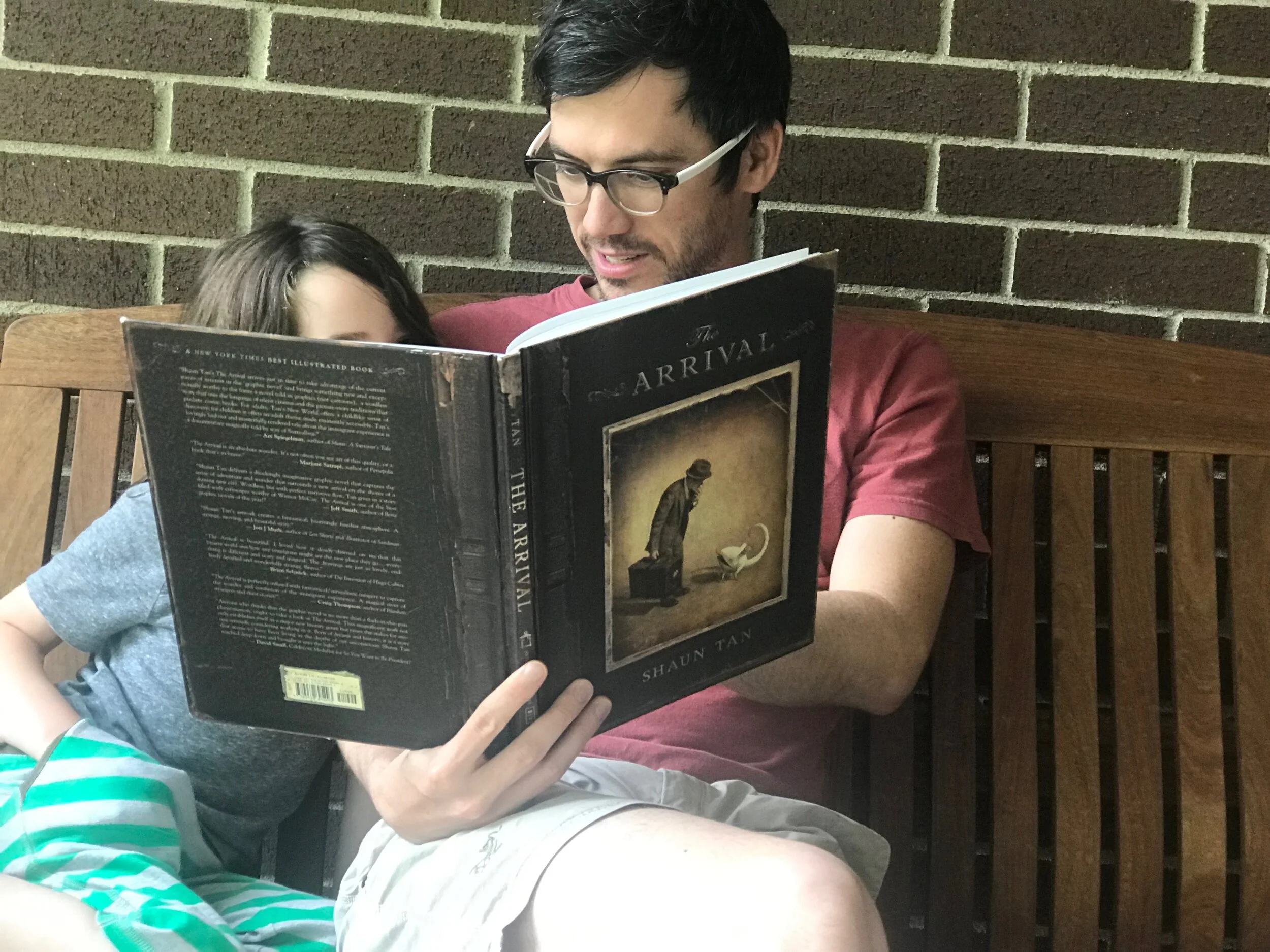

This is exactly why it’s incredibly important to develop a habit of dialogic reading with kids - a style of read alouds I’ve written about before. The basic idea is that you need to open up a dialogue while reading - with lots of questions and observations. And this couldn’t be more important than when you’re reading books with moral lessons in them. Especially if those lessons aren’t crystal clear and slapping you in the face - and I mean verbatim. Remember, in many cases we’re talking about toddlers here, and I implore you not to simply assume that the message always sinks in correctly.

In fact, the real reason I wanted to write about the importance of talking about the books you read together is that, sometimes, the completely wrong message sinks in instead. Think back to what I said about sarcasm - it’s almost impossible to make sense of for a new brain. Although kids learn quickly and are constantly learning about the world around them, you have to admit there’s a big learning curve with some concepts.

And let’s not forget that a child’s frontal lobe is far from developed, and for that reason attention and focus is never a guarantee. In that case, dialogic reading - maybe pausing to ask a few questions - is not merely a strategy to maintain focus on story time, but also to make sure that very important chunks of the story (and perhaps the moral lesson itself) aren’t simply tuned out entirely.

Imagine if you were reading a book to a wiggly 2-year-old, and the only section of the book they tuned in for was the “obviously” questionable opinions of the “obvious” villain of the story? Well I don’t have to imagine it, because that’s exactly what happened to me with my daughter. And that’s exactly the reason I want to encourage parents and teachers to keep an open dialogue during and after story time.

In fact, this fundamental confusion of the lesson from a story has already happened two very clear times to us. The first time it happened was with a wonderful book called A Day in the Life of Marlon Bundo. If you’re unfamiliar with the book, it exists as something of a gag made by Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. Marlon Bundo is the actual name of the ex-president Mike Pence’s rabbit, and in this book Marlon Bundo falls in love with another boy bunny.

So this book is actually a very sweet champion of LGBTQ rights with the important message of following your heart and being yourself. I highly recommend it. Mike Pence even gets something of a cameo as a stink bug, who says the bunnies can’t get married because they are both boys. From my perspective as an adult, paying good attention to the entire book and knowing everything about the backstory, nothing could possibly be clearer than the fact that the stink bug was the villain, and we were all collectively jeering him and making fun of him.

But apparently I was wrong, because my daughter was about 2 years old when I read it to her, and apparently the message was not the clearest thing in the world, and didn’t exactly sink in correctly. About a week later, the subject of marrying whoever you fall in love with when you grow up came up again somehow, and my daughter confidently interjected, “but the stink bug said boys can only marry girls.”

Somehow, someway, the entire concept of the stink bug being the bad guy went over her head. Looking back, it’s highly possible she was drifting in an out of consciousness the entire time I was reading the book to her (or perhaps her attention was elsewhere), because she was 2 after all. For all I know, the only page she even heard was the single page where the stink bug stated that boys marry girls.

Whatever the case may be, it’s just about the most unfortunate example I can think of of the wrong message sinking in. And hopefully it can serve as a strong reminder of the importance of dialogic reading and discussing what a book is about with little ones - especially when comprehension is so important.

Another more recent example in our house comes from the amazing book The Barnabus Project by The Fan Brothers. I absolutely adore this book, and we made it our book of the year last year for the Dad Suggests Picture Book Awards. It tells the tale of a group of failed experimental animals - like a cross between an elephant and a mouse - that live deep underneath a pet store called Perfect Pets in a secret lab.

What we have here is a beautiful commentary on what perfection and imperfection means, and how little it does or should define us. Clearly these “imperfect” animals trying to escape from the laboratory are easy to fall in love with, because we as readers fall in love with them quickly and cheer for them and try to learn all of their names (like my son did). But it’s the animals above in the pet store who are called the perfect ones.

It’s a deep concept for little ones no doubt, but it’s an important one. We’re talking about superficial “perfections” that have no real meaning. And we’re talking about happiness and love and friendship and uniqueness and a place to feel like you’re home and you belong. It’s about what makes us who we are, and that’s admittedly a lot to ask a kid to take away from a picture book.

Perfect is such a loaded word, and when Barnabus the half elephant/half mouse sees his “perfect” counterpart in the Perfect Pets store, he himself even claims it to be perfect. So when I lobbed up what I thought to be a softball question - “would you pick an imperfect pet from the lab or one of the perfect pets from the store” - it shouldn’t really surprise me what my daughter said. She wanted the perfect pet with the cotton candy skin!

That’s when it struck me that perhaps we missed something about the conversation of imperfections and identity. Imagine if I allowed her to walk away thinking this book was about how cute and attractive things are perfect. Another scary example of extracting the exact wrong message. Clearly she was feeling bad for Barnabus on this particular page, even wishing aloud that he too would be perfect and cotton-candy-like one day. And you can be certain we dug a little bit deeper together after that - and we had a good talk about what makes us who we are, what perfect means, and what really matters in this life.

And for me that’s very often what I think about when it comes to being a dad. I feel like it’s my duty to help my kids navigate certain experiences and digest certain lessons. And books can actually be a beautiful source of those life experiences - packaged into a beautiful and thoughtful works of art. They can serve as a very effective messenger of very important lessons. But by no means does that mean parents and teachers are off the hook when the read aloud is over. Because I’ve learned without a doubt that those followup conversations are just as vital.

Do you do dialogic reading with your kids and have conversations during or after reading? Do you have any funny examples of young ones misinterpreting the books you read? Let us know in the comments!